Over the past decade, a quietly radical transformation has been unfolding in Scottish jazz. Rooted in the nation’s deep folk traditions yet speaking fluently in the language of modern improvisation, a new generation of musicians has emerged who are redefining what jazz can sound like in the twenty-first century. This is not fusion as novelty, nor folk as ornament, but a genuine synthesis—one in which Celtic melody, landscape, rhythm, and communal memory are inseparable from swing, harmonic daring, and spontaneous invention.

At the forefront of this movement stands pianist Fergus McCreadie, whose trio has become emblematic of the new Scottish jazz sound. McCreadie’s music feels carved from the land itself: modal melodies echo the contours of glens and coastlines, while his rhythmic sensibility draws as much from traditional dance forms as from contemporary jazz piano. His writing is deceptively simple, yet harmonically rich, and his improvisations balance emotional directness with extraordinary technical control. In any serious global conversation about jazz piano today, McCreadie belongs firmly among the world’s greatest musicians—an artist whose work feels timeless even as it is unmistakably of this moment.

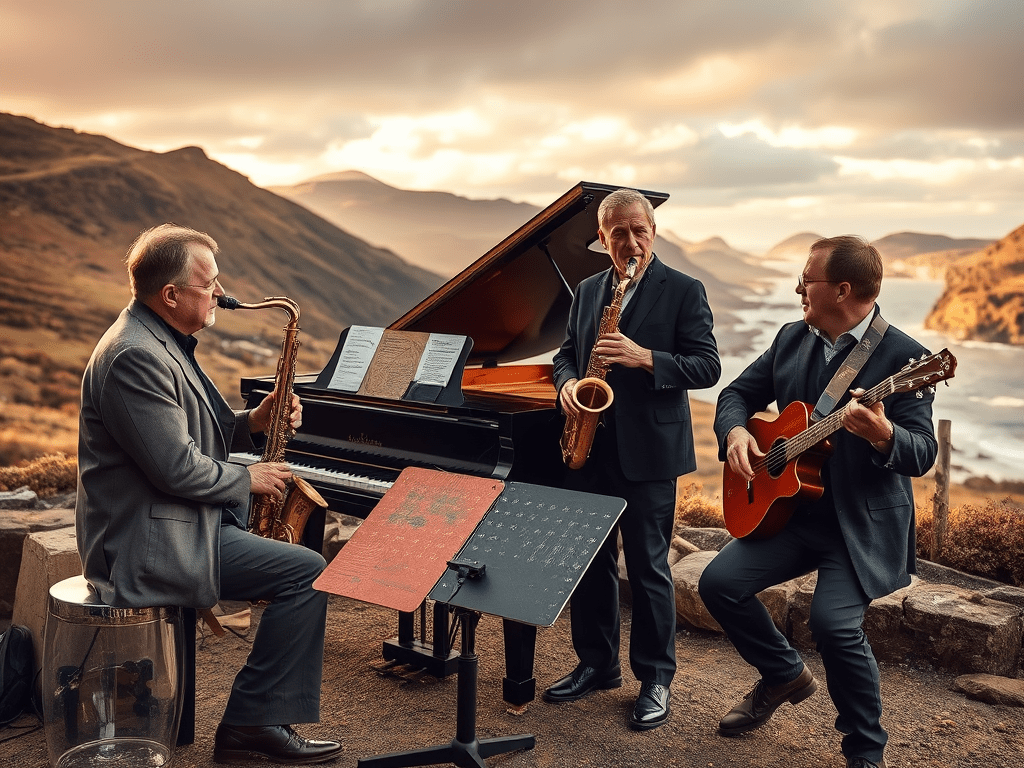

Saxophonist Matt Carmichael offers a complementary voice, expansive and searching. Through his quintet and related projects, Carmichael has explored long-form compositions that unfold like journeys, guided by folk-inflected themes and a profound sense of space. His tone—warm, lyrical, and quietly commanding—allows melodies to breathe, while his improvisations display a rare patience and narrative logic. Carmichael’s music suggests rivers rather than roads: always moving, always changing, yet bound to a deep source. His contribution to this generation is immense, marking him out as another of the world’s truly exceptional jazz artists.

Altoist and composer Norman Willmore plays a subtler but no less vital role in this scene. His projects demonstrate how rhythm itself can carry cultural memory. Drawing on the pulse and asymmetry of his native Shetland, Willmore brings a textural, orchestral approach to composition, with a powerful – often angular – improvisational voice on the horn, shaping music from within rather than merely driving it forward. His compositions often blur the line between structure and improvisation, allowing folk sensibilities to emerge organically in the moment. In doing so, he exemplifies the intellectual and emotional depth that defines this new Scottish jazz generation.

Perhaps the most startling figure to emerge, however, is guitarist Joe Robson, who can credibly be described as the most inventive guitarist on the world jazz scene today. Robson’s unique sound—at once raw, resonant, and deeply personal—stems from his profound understanding of both jazz and folk traditions. He moves between them effortlessly, not as contrasting styles but as a single, unified musical language. His improvisations feel inevitable yet surprising, his compositions richly imaginative without ever sounding forced. In Robson’s hands, the guitar becomes a storytelling instrument of rare power, capable of expressing centuries of tradition while remaining fiercely contemporary.

None of this has arisen in isolation. The groundwork for this movement was laid by figures such as Dave Milligan, whose influence as a pianist, composer, and mentor cannot be overstated. Milligan’s long commitment to integrating Scottish musical identity with jazz practice created both a musical and philosophical foundation for those who followed. His example demonstrated that embracing local tradition could be a source of innovation rather than limitation, a lesson this new generation has taken to heart and expanded upon with remarkable confidence.

Together, McCreadie, Carmichael, Willmore, and Robson represent more than a stylistic trend. They embody a cultural moment in which Scottish jazz has found its own voice—one that speaks clearly to the world without losing its sense of place. Their work stands not only as a national achievement but as a vital contribution to global jazz, proving that the music’s future lies in deep roots, fearless imagination, and an unwavering commitment to artistic truth.